The Jersey Law Review - February 2004

ANY FRIDAY IN THE SATURDAY COURT

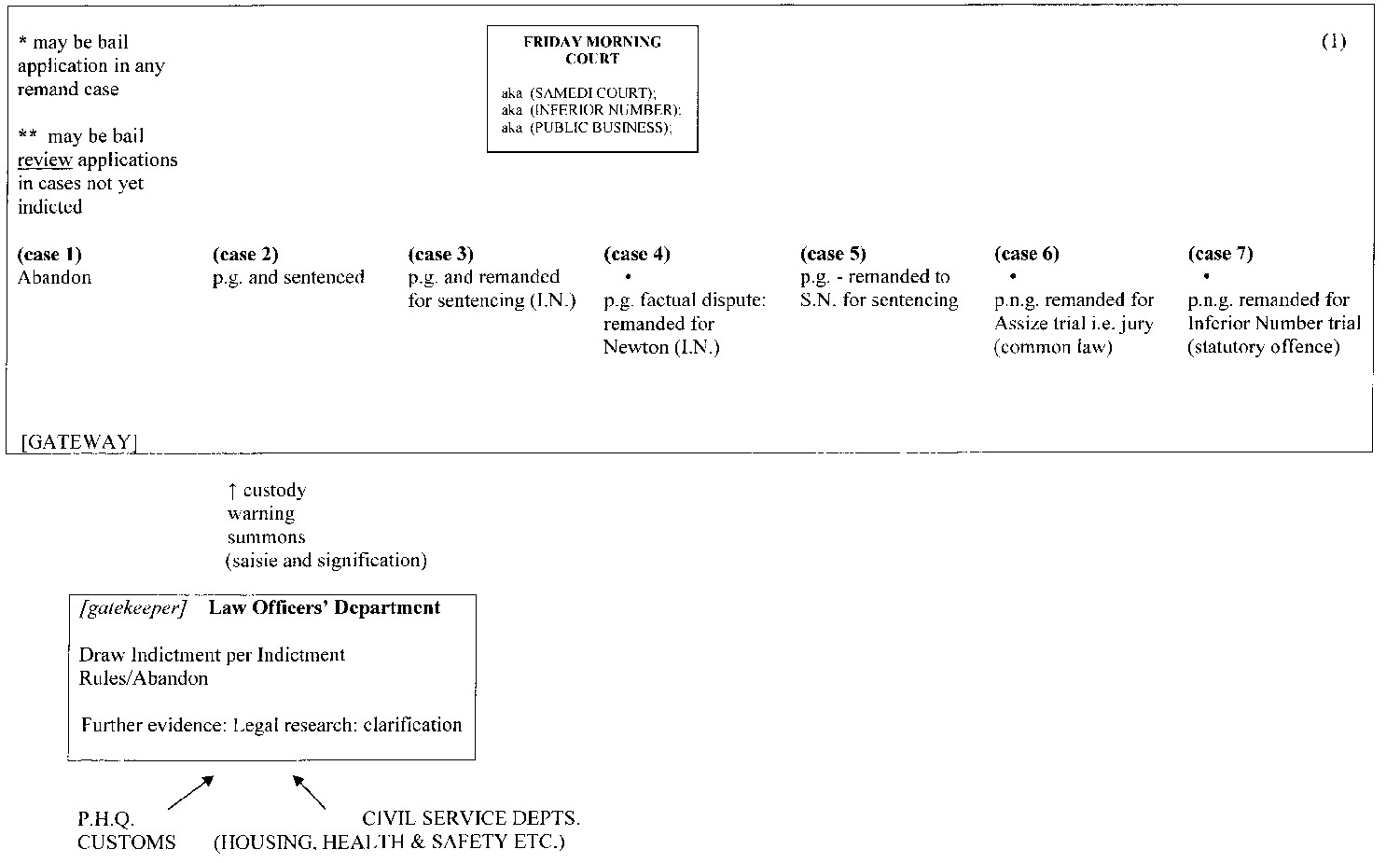

Cyril Whelan

1 In

2003, as part of the in-house training programme at the Law Officers’

Department, a series of discussions about Royal Court criminal procedure was held. During those sessions it became

increasingly clear that a useful way of visualising the various paths and

centres of the criminal process was to concentrate upon the contents of a Crown

Advocate’s briefcase on any given Friday morning in the Samedi division. In that way it was easy to see the

criminal part of the public business list on a Friday morning as a gateway at

which some cases are dealt with, and through which others pass in order to

reach a different level of activity.

2 What

follows is an abstract of the training observations which were offered at the

in-house sessions. It is quite a

good idea to keep a thumb in the page with the chart at the end of this

article. At the bottom of the chart

coming into the Law Officers’ Department from the left and the right are

case files. Those coming in from

the left are from the uniformed services, generally the Police and Customs. Those coming in from the right are from,

what it is convenient to call, civil service departments - characteristically

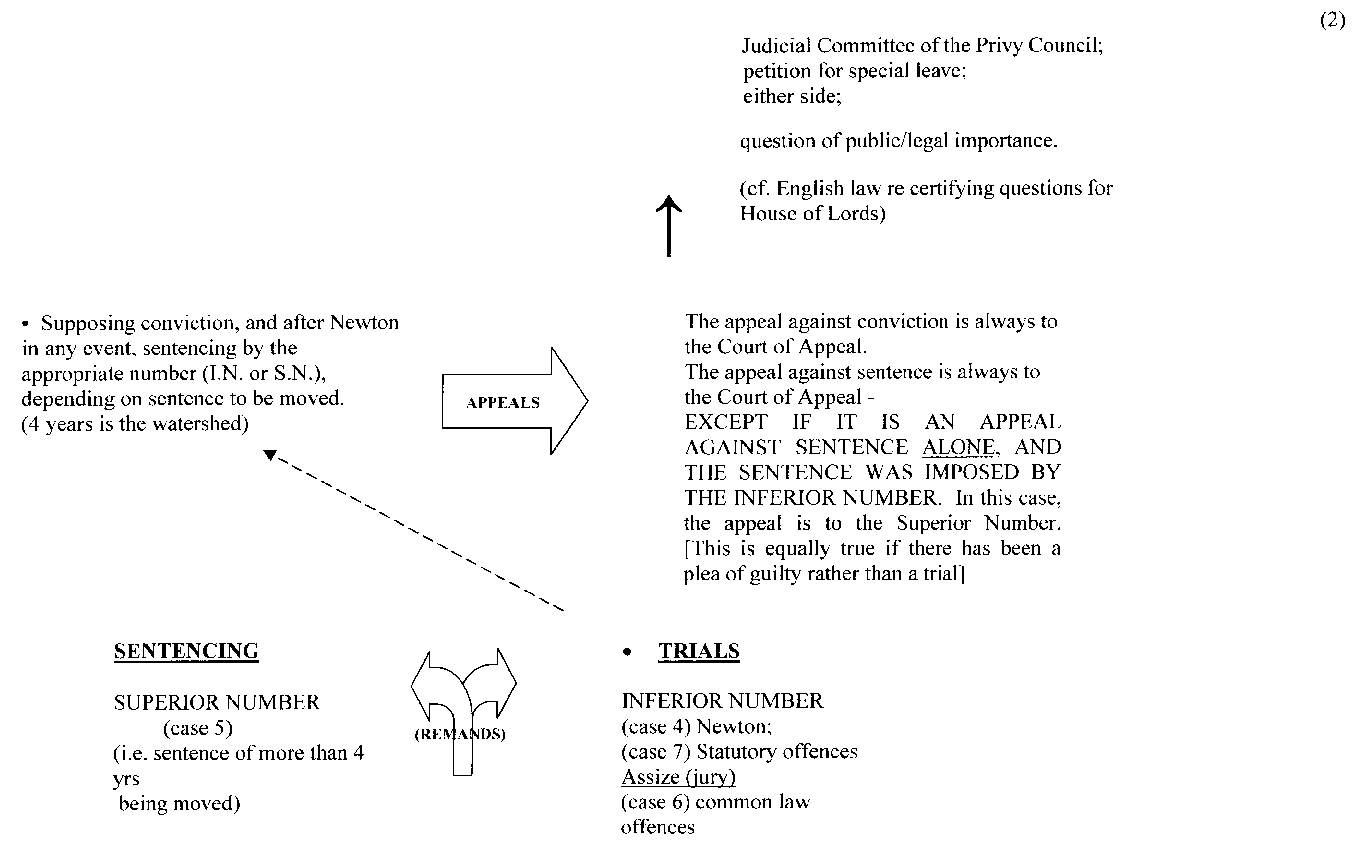

Housing, Social Security, Health and Safety and Income Tax – although increasingly

files are coming from the Jersey Financial Services Commission, which is not a

civil service department.

3 It

is important to understand that when these files come into the Law

Officers’ Department they are pretty much unrefined. A case file is essentially a lever-arch

file containing a series of witness statements and key documentary and

photographic exhibits. It is

covered by a report of the investigating officer.

4 Those

that come in from the uniformed services will have been through the

Magistrate’s Court and therefore come up after committal. That means no more than that they have

passed the lowest available test in the criminal law, namely the establishment

of a prima facie case. A magistrate

has seen enough to convince him that the matter has the appearance of

criminality and should be referred to the fuller process of the Royal Court. One should remember that in the case of

a paper committal the magistrate has not even reached that

low level conclusion - it has simply been accepted by defence counsel.

5 Files

coming in from the civil service departments for the usual range of statutory

offences have not even been through the committal stage. No person in legal authority has ever

seen the case file before. It comes

into the Law Officers’ Department from the hands of a civil servant. This is not to say that it is anything

other than professionally prepared.

6 In

the box marked Law Officers’ Department on chart (1) the Department is

referred to as ‘the gate keeper’ because essentially the files are

examined and worked on to see whether they are fit to proceed onward to the

gateway of Royal Court process, in what form, and what needs to be done to get

them fit. This work identifies any

cases that are not fit to proceed and can never be made so. Represented at the bottom of the Law

Officers’ Department box is the work of a member of that department

examining the file and, for example, making enquiries with those at Police

Headquarters, commissioning extra information, identifying any need for extra

statements to be taken or other work done, and doing the legal research

necessary to see whether and if so, in what form, the case should be indicted.

7 Above

that in the box will be seen the word ‘Abandon’. It happens from time to time that the

conclusion is reached that the case cannot proceed because a vital legal

ingredient is missing or, to take another example, because a witness cannot be

found. Above that in the same box

is shown the crucial drawing-up of the indictment. This is where the rules

start to have a crucial importance.

An incorrectly drawn indictment can cause a case to fall to the ground

from the outset, at the close of the prosecution case, at the close of the

defence case, or on appeal.

Adherence to the Indictments (Jersey)

Rules 1972, as amended, is vital.

8 It

is important to note that the Attorney General can indict for any offence which

is disclosed by the evidence which has come to him in the case file. There is sometimes no resemblance

between the charge on which the accused was committed by the magistrate and the

indictment on which he is prosecuted by the Attorney General. Because the Attorney General reshapes

the charge sheet - perhaps bringing entirely different

charges - this is not an occasion for the defence to be granted costs.

9 In

the case of the civil service files, e.g. Health and Safety, all of the

stages which have just been described take place. There is, however, a slight difference

in form. A company which is being

prosecuted for a breach of the health and safety laws, for example, is not

indicted. Instead, it is sent a

summons which specifies the charges and it is required to answer that summons

by appearing in court on the appointed day. For court purposes the summons is turned

into a billet (not an indictment) and it is the billet which is

read and to which the company pleads.

10 At

this point, then, the work has been done in the Law Officers’ Department

- decisions have been taken, cases have been studied, indictments or summonses

have been drawn up and all of the matters now have to proceed. The gatekeeper has done his work and it

is time for the cases to move forward to the gateway of the Royal Court. How are the cases brought to that

gateway? Linking the box showing

the Law Officers’ Department and the box showing the Royal Court will be seen

an arrow with the words ‘custody, warning, summons (saisie

and signification)’. All

this means in practical terms is the following: that if the person to be indicted is in

custody, the prison is notified that he or she must be brought down to court on

a certain date at a certain time; if he is on a warning, i.e. bail with

a warning to come to court when required to do so, then he is formally notified

by the police that he must appear in the Royal Court on a certain date at a

certain time. If it is one of those

statutory offences, a Housing, Social Security, or Health and Safety infraction

then, as already mentioned, the notification is done by way of summons. The

summons is formally served and in the text of the summons which sets out the

charges is a requirement notifying the company that it must be represented by a

director in court on a certain date at a certain time. Included on the chart is the process

known as ‘saisie and

signification’. It is not

terribly important in practical terms.

But the power does still exist and has been used on rare occasions,

really as a method of last resort.

It is the power of the Attorney General to direct a police officer to

arrest someone immediately and to have him brought without

any more formality before the Royal

Court at the first opportunity.

11 In

the ways described, then, the cases are brought into the Royal Court. Friday morning court is a classic

institution and is very much the gateway into the whole of Royal Court process. Cases may be dealt with at the gateway

itself or may proceed from there on a longer journey.

12 If

one looks at the Friday morning court box on the chart one sees that the Crown

Advocate has brought seven cases files to Court; he or she therefore has just

about one of everything that can happen.

If one looks at the bottom line of the Royal Court box one sees that in the Law

Officers’ Department the gatekeeper decided that the case (case 1) did

not make the grade for some reason and therefore it is abandoned. The accused has to be there, the

abandonment has to be formally announced and as often as not the defence gets

its costs without argument. The

accused is free to go. The

abandonment is usually announced either because there is insufficient evidence, or because a

prosecution is not in the public interest.

13 In

the second case the indictment is read to the accused and he pleads guilty to

it. Because all the work has been

done and the necessary background reports are available and because the

prosecution is not moving conclusions of more than four years, sentencing can

proceed immediately. It does not

matter whether this is a common law or a statutory offence. The Crown is simply in the Inferior

Number moving for a sentence within the jurisdiction of that court. The accused is therefore appearing

before the Bailiff and two Jurats as a sentencing

court for these purposes. Once the

accused has pleaded guilty the Crown Advocate will read out a summary of the

facts of the offence; the Crown Advocate will point out the accused’s

personal circumstances, including any criminal record; the Crown Advocate will

refer to some previous sentencing decisions of the Jersey courts or - if

appropriate - the English courts

(usually guideline cases only, whether Jersey or English) and the Crown

Advocate will move the Attorney General’s conclusions which, because the

case is in the Inferior Number, must be for four years’ imprisonment or

less. The defence advocate will

then speak in mitigation usually seeking to minimise the

facts, accentuate the positive aspects of the accused’s character and

antecedents and usually seek to argue down the prosecution’s conclusions

either in kind (by moving for probation or a fine rather than a sentence of

imprisonment) or in quantity (accepting that the offence really does merit

prison but not as much as the prosecution has moved for). The Court then retires to

deliberate. Sentence is a matter

for the Jurats alone. The Bailiff has no voice in it. The only time that is not true is when

the Jurats cannot agree between themselves. The Bailiff then gets

the casting vote and is not obliged to cast it in any particular direction, i.e.

he is not bound by any convention to move for the more apparently lenient of

the options. The Bailiff and Jurats then come back into court and announce the

sentence. These days it is

incumbent upon the Bailiff to give a short reasoned judgment as to why this

particular sentence is being imposed. If a court is dealing

with a young offender then the additional formalities contained in the Criminal

Justice (Young Offenders) (Jersey) Law,1994

have to be observed.

14 In

the third case which is in court, again the accused pleads guilty to the

indictment which is read out to him.

This time, however, the Probation Service and/or other background

people, e.g. psychologists, have not completed their reports. The Crown Advocate knows that in any

event the Crown will be moving for a term of imprisonment which does not exceed

four years, so that sentencing will eventually take place in the Inferior

Number i.e. when the reports are ready. It is therefore a case of putting the

case off for, say, four weeks so that the background reports can be completed,

with the accused being remanded until that date on the appropriate (usually the

existing) terms. Alternatively, if

the offence to which he has just pleaded guilty is a serious offence, the Crown

Advocate is likely to move that the accused should be remanded in custody even

though thus far he has been on bail.

In four weeks’ time this case will come back before this same

court - the Inferior Number - and sentencing will take place according to

exactly the same procedure as was described in paragraph 13 above.

15 In

the fourth case the indictment charges the accused with a grave and criminal

assault. He pleads guilty but says

that he acted under severe provocation from the

victim. Although that is not a

defence, it may be very significant mitigation to keep the sentence down. However, it is the prosecution case that

this was a completely unprovoked assault by a drunken accused on a victim who was

a complete stranger to him. Because

the issue goes so directly to the level of sentence likely to be imposed, it

has to be resolved by a trial process.

Therefore the Crown Advocate accepts the plea of guilty, but indicates

to the judge that there is a dispute about the factual basis upon which the

accused is to be sentenced. The accused is then remanded to a pre-arranged date

so that the Newton

trial of that issue can take place on that date.

16 In

the fifth case the indictment is read and the accused pleads guilty to a

multi-count indictment of serial sexual abuse of children, including sodomy,

over a course of years. It is

perfectly apparent to all that the sentence for which the Attorney General will

now move will be in excess of four years.

That makes it the preserve of the Superior Number for sentencing. The Crown Advocate therefore moves that,

having pleaded guilty, the accused be remanded to appear in the Superior Number

(Bailiff and at least five Jurats) for sentencing on

a date which has been pre-arranged and which is now announced to the

court. Again, the question of the

terms of the remand - custodial or on bail - will arise for consideration.

17 In

the sixth case the indictment is read out to the accused. It charges a string of offences of

breaking and entering and larceny.

He pleads not guilty to each of the offences. There will have to be a trial and,

because the offences charged are common law offences, that trial will take

place before a jury at Assize. Again, the Crown

Advocate knows that date by pre-arrangement with the Bailiff’s Judicial

Secretary and he announces it to the Court asking for the accused to be

remanded until that date to stand trial before a jury. Again the question of a custodial remand

or remand on bail/a warning arises.

18 In

the seventh and final case that Friday morning a large firm of building

contractors is charged with a serious breach of the Health

and Safety laws which has caused one of its workmen to suffer a fractured spine

and severe injuries to both feet.

The company is represented by one of its directors; the billet (not

the indictment - this is one of those ‘civil service’ cases that

have come in from the Health and Safety section of the Employment and Social

Security Department) - is read and through counsel the director on behalf of

the company will indicate whether or not the infraction is admitted. Here the infraction is

denied and, again, there has to be a trial. But this time, because it is a statutory

offence, it will be a trial not before a jury at Assize but before the Inferior

Number, sitting not as a sentencing court but as a court of trial (i.e. en

police correctionnelle). That means that the company, on a future

day, will re-appear before this very court (Bailiff and two Jurats

- although it does not have to be the same individuals) and there will be a

criminal trial in the fullest sense, the only true distinction being that the

two Jurats will form the tribunal of fact and not a

randomly selected jury of twelve members of the public. Again, by a pre-arrangement, the Crown

Advocate knows the trial date and now announces it to the court. The court remands the matter until that

date. Because the accused is a

company, there is no question of there being a custodial remand.

19 If

one looks to top left-hand corner of the box one will see firstly that there

may be a bail application made by any individual who is remanded; and then at

the double asterisk one sees that also on the list may be separate bail review

applications from the Magistrate’s Court in cases which have not yet been

indicted and found their way to this gateway occasion in the Royal Court. There is a crucial distinction between

the criteria which apply before the Royal Court is seized of the case on

indictment (review) and those which apply after the Royal Court is so seized

(consideration de novo).

20 That,

then, is a brief account of the whole range of activity which is going on at

this busy Royal Court gateway on any Friday morning so far as concerns criminal

cases.

21 Taking

things in sequence as they appear on the chart, it is time to consider what

happens to those cases which pass through the gateway of the Friday Court and

are remanded up into higher levels of the criminal process,

rather than being dealt with at that gateway point.

22 If

one thinks about it, that remand out of the Friday Court can only be for one or

two purposes, either for sentencing or for trial. If one looks at the chart then, the

movement up out of the Friday Court box, on the left is the sentencing remands

to the Superior Number. In this

case it is case 5 from the Friday morning. It will be recalled that on the Friday

morning the accused pleaded guilty to a string of serious offences and was

remanded to the Superior Number for sentencing. There it is on chart (2). His sentencing takes place in front of

the Superior Number (Bailiff and at least five Jurats,

i.e. any number of Jurats between five and

twelve). He is being sentenced now

in this Court because the prosecution is going to recommend by way of its conclusions

that he should receive a term of imprisonment of more than four years. The sentencing process which has been

described in respect of case 2 down in the Inferior Number on that Friday

morning is exactly the process which now takes place in this Court, the

Superior Number. The only

difference is the number of Jurats. The rationale is probably no more than

this: if the prosecution is asking

for a seriously heavyweight sentence, then scrutiny by a wider selection of

judicial opinion is desirable. The four

year figure is more or less arbitrary as a watershed. Once it was three years, and before that

it was two. The selection of the

break point must be supposed as much as anything else to be based on

logistics. There are many more

practical difficulties in convening five and more Jurats,

given their commitments, than there are in convening just two Jurats; thus the extension of the Inferior Number

jurisdiction.

23 Looking

to the other side of the diagram at this level there are the trials. These matters have been remanded up out

of the Friday Court process because a quite different level of activity is

required. In ascending order there

is first the centrepiece of the criminal process, the jury trial (still

referred to as an Assize trial in Jersey). That is case 6 from this Friday morning

court. The accused has pleaded not

guilty to the common law offences charged against him and it is the jury who

must now decide whether he is guilty or not.

24 Then

there is the other sort of trial which will take place is case 7 from the

Friday morning Court. There, it

will be recalled, the company has denied a serious offence and that issue has

to be decided by a tribunal of fact. In this case, because the offence is

statutory, the company has no option of being tried by a jury as the tribunal

of fact. Instead it will be tried

by the Bailiff and two Jurats, i.e. by the

Inferior Number sitting en police correctionnelle. Just as in a jury trial, the Bailiff is

the judge of law but the facts are for the tribunal of fact, in this case the

two Jurats.

If the two Jurats are split on the issue of

guilt the Bailiff becomes a judge of fact and gets the casting vote. Again he is not bound

by convention to cast it in one particular direction or another. He simply votes on the issue of fact

according to his conscience and his view of the evidence. The internal procedure which governs

this sort of trial is in large measure indistinguishable from the procedure

which takes place in front of a jury.

25 Finally,

under this trial heading remanded out of the Inferior Number on the Friday

morning, comes case 4. This was the

case in which the accused has pleaded guilty to the grave and criminal assault

but claims that he was provoked and, in the light of that provocation, that he

should receive a much lighter sentence than would be the case had there been no

provocation. The Crown’s case

is exactly that, i.e. there was no provocation so that the reductive

effect that the accused is trying to establish is not in truth present on the

facts. This is the so-called

‘Newton’

hearing (Newton

did not in fact get a hearing). I

have listed this under the trial heading very deliberately. A Newton

hearing is a term of convenience and nothing more. It is absolutely vital to appreciate

that this is a trial in the fullest and most absolute sense. That is why the expression ‘Newton

trial’ is to be preferred to a ‘Newton hearing’ because it

reminds one that this is nothing more and certainly nothing less than a

trial. The burden of proof is

always on the prosecution and the standard of proof is the criminal

standard. Vitally, it can be said

that the essential procedure should be indistinguishable from that which takes

place at a jury trial.

26 That,

then, is the trial level of activity within the Royal Court procedure. The broken arrow going upwards on the

chart shows what happens after a trial.

If the accused has been acquitted, then he walks away and the defence,

in most circumstances, has its costs.

But here on the diagram it is supposed that there has been a

conviction. It follows that the

accused has to be sentenced for the offence(s) of which he has been found

guilty. When the verdict is announced, the prosecution simply moves that he be remanded

to a pre-arranged date so that there can be a separate sentencing

occasion. That sentencing occasion

will be either in the Inferior Number (so that the accused may feed back into

the Friday morning Court occasion for sentencing) or he will be remanded for

sentencing by the Superior Number and will undergo exactly the same process in

the Superior Number as case 5 underwent, which shows on the diagram and about

which mention has already been made.

Again, the choice of court will depend upon the level of sentence for which

the prosecution proposes to

move. And again, following

conviction and before sentence the accused may make an application for bail. In a case which is likely to attract a

prison sentence the granting of bail is still to be regarded as somewhat

exceptional at this point of the process.

27 Thereafter,

i.e. once the accused has been convicted and then sentenced, the

question of appeal arises. To which

court he appeals is a difficult question depending upon which Court he was in

and what sort of appeal he wants to make.

On the diagram, opposite the arrow with ‘APPEALS’ on it, the

question has been reduced to a single formula -

(1) the appeal against conviction is always

to the Court of Appeal;

(2) the appeal against sentence is always to

the Court of Appeal - except that if it is an appeal against sentence alone, and

the sentence was imposed by the Inferior Number, the appeal is to the Superior Number. This remains true even if there was a

plea of guilty, rather than a trial.

28 Upwards

from that Court of Appeal stage is an arrow on the diagram showing the

possibility of a further appeal to the Judicial Committee of Privy

Council. That is something of a

specialised rarity. It is probably

sufficient for present purposes to say that the Privy Council option is open

both to the prosecution and the defence.

The key procedural point is that the jurisdiction of the Judicial

Committee of the Privy Council is a prerogative jurisdiction. An applicant therefore

needs the special leave of Her Majesty in Council under rule 2(b) of the

Judicial Committee (General Appellate Jurisdiction) Rules 1982 to bring what is

in essence a petition of appeal.

Leave is likely to be granted only in those cases

where there is a crucial point of public/legal importance to be

considered. There is the broadest

of analogies - although the test is likely to be far more stringent - with the

process in England

of asking the Court of Appeal to certify a point of public importance for the

consideration of the House of Lords.

29 One

gets a sense of the sort of issue with which the Privy Council will involve

itself, and the mode of its approach, if one reads Renouf v Attorney General

for Jersey.

30 The

most recent criminal case to go to the Privy Council from Jersey

(and thence to Europe) was Snooks

v Att.Gen.. The issues which fell

for consideration in that case were fundamental, structural, and systemic - how

should an Inferior Number trial, before Bailiff and two Jurats,

be conducted? Was the existing

time-hallowed procedure acceptable in the modern world? Did it accord with standards of fairness

as they have become generally to be recognised? For Privy Council purposes the distinction

one is trying to draw is between issues of this sort which go to the very

foundation of our law and procedure - and on the other hand run-of-the-mill

issues which although important in themselves arise in nine out of every ten

appeals - was the sentence too high, was the identification evidence reliable,

was there a breach of a PACE code and if so was it fatal, was a piece of key

evidence inadmissible? All these

important questions are the province of the Court of Appeal and there the

matter is usually left to rest. It

is only cases of the Renouf or Snooks

sort which raise the most fundamental questions about the foundation of Jersey law or procedure that are likely to find their way

through the filter and into the Privy Council.

Cyril Whelan is an

advocate of the Royal Court and is a Principal Legal Adviser in the Law

Officers’ Department, Jersey. He is the author of ‘Aspects of

Sentencing in the Superior Courts of Jersey’

and other works. He has been a Crown Advocate since 1998.