Damages

REFORM IN Jersey

Robert

MacRae

Prior

to the enactment of the Damages (Jersey) Law 2019 there had been little

statutory intervention in Jersey in respect of the award of damages in personal

injury cases. The Damages (Jersey) Law 2019 changes this. It creates a regime

for setting the “discount rate” for future pecuniary losses,

together with a power to order periodical payments, even in the absence of

consent of the parties. It has introduced a good deal of certainty in an area

of law that was hitherto uncertain.

Introduction

1 The Damages (Jersey) Law 2019 (“the

Law”) was lodged au Greffe by

the Chief Minister on 24 October 2018, adopted by the Assembly after debate on

29 January 2019, and came into force on 3 May 2019.

2 It is a short Law of only seven articles,

but its importance belies its length. It makes provision for compensation in

personal injury cases by requiring (for the first time in Jersey) courts to

apply a specified discount rate for future pecuniary losses and also creates a

statutory regime for awarding damages by way of periodical payments. Both the

discount rate and periodical payment orders are matters upon which many other

jurisdictions either have legislation or are considering legislation and the

Law represents a substantial reform which has already had a significant effect

in personal injury cases.

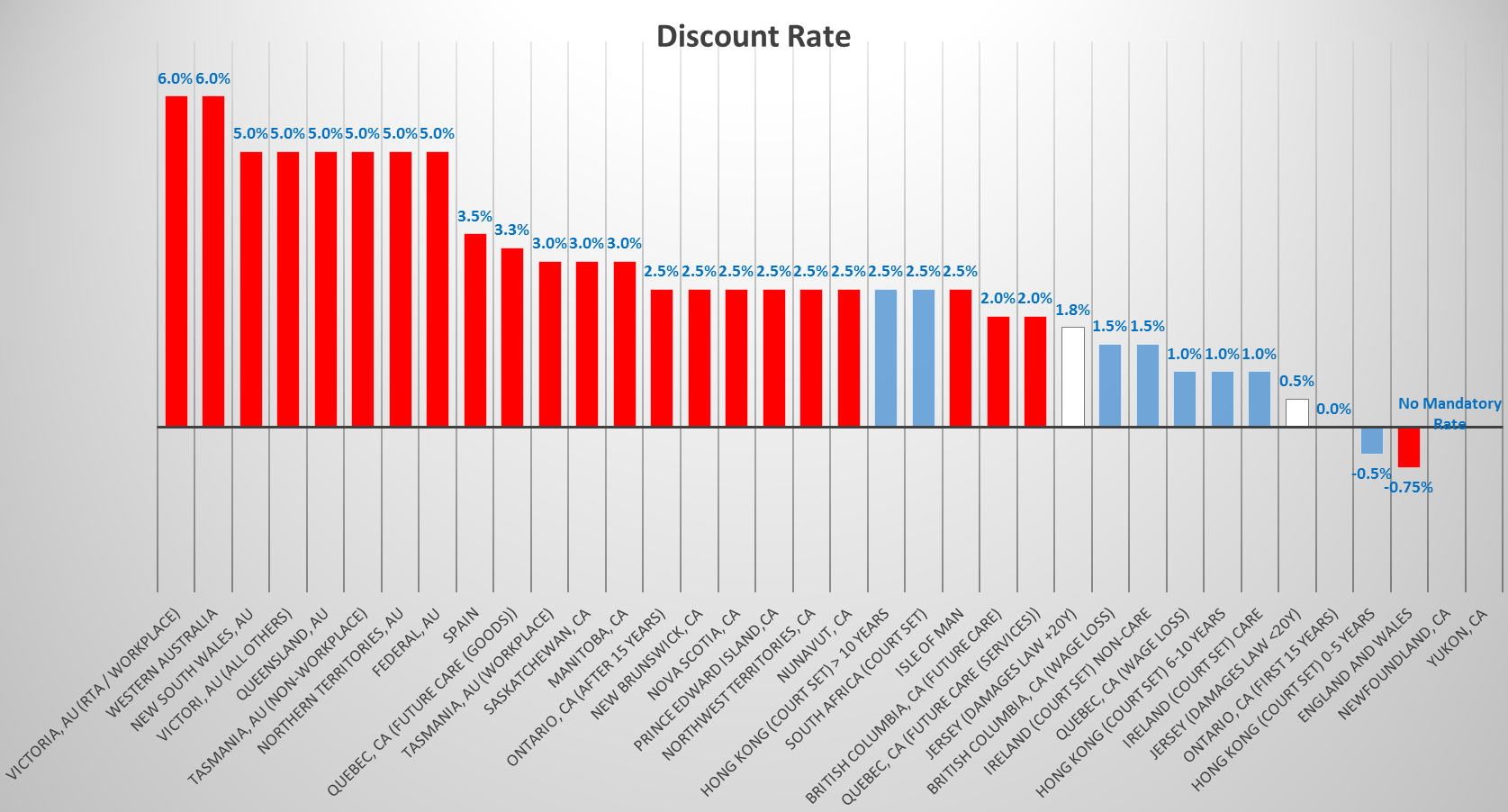

Background

3 The Law concerns awards for damages for

personal injury. Damages awarded by a court ought to be sufficient to cover the

loss and expense occasioned by the injury.

4 In calculating damages in personal injury

cases, the Jersey courts have often chosen to follow the principles established

by the English common law.[1] This

includes having regard to the decision of the Privy Council on appeal from the

Court of Appeal in Guernsey in Simon v

Helmot namely, per

Baroness Hale:[2]

“[T]he claimant should receive full compensation

for the loss which he has suffered as a result of the defendant’s tort—not

a penny more, but not a penny less.”

5 Accordingly, the plaintiff should receive

full but not excessive compensation. In many cases there will be uncertainly as

to the cost of future care; how long the victim might need care; and advances

in medical science which may increase or reduce the cost of care.

6 Ultimately, when determining an

appropriate lump sum award for a plaintiff whose claim includes future

pecuniary losses, the court needs to come to view as to:

(a)

life expectancy;

(b)

costs of future care;

(c)

the effect of inflation on the costs of care; and

(d)

investment returns on the award of damages, which includes considering both

what sort of investments are appropriate in terms of risk and the returns that

might be gained on those investments.

7 The difficulty in awarding damages is

that it is not possible to know exactly how much a plaintiff will need when

damages are assessed. Even if the cost of care required in any case is agreed,

it is not known how much money needs to be awarded today to pay for it when it

is needed in the future.

8 For good reason it is recognised that the

only certain thing about an award of damages in these circumstances is that it

will be too much or too little, see D v

Greater Glasgow Health Board.[3]

The discount rate

9 The discount rate is a method by which

the future pecuniary losses included within a lump sum award are adjusted to

take account of the predicted return on investing the lump sum awarded to the

plaintiff and any inflationary considerations which may affect that predicted

return. Article 1 of the Law defines the discount rate as:

“the rate of the return from the investment of a

sum awarded as damages for future pecuniary loss in an action for personal

injury.”

10 It is recognised that the setting of a

discount rate for use in personal injury cases is not a straightforward

exercise, and that the outcome is very important to all those affected; both

the victims and their families and, on the other hand, insurers and uninsured

defendants and, in certain circumstances, the state. If the discount rate is

too great, then a lack of investment return or erosion of value through

inflation could cause the plaintiff to run out of money in his or her lifetime.

But if the discount rate is set too low, then damages will be higher than

required, leaving a surplus when the victim dies—a surplus funded by

defendants and/or their insurers. Eliminating all risk to particular plaintiffs

might, for example, come at considerable cost to the wider economy or the

provision of public health services.[4]

11 In England and Wales, the 1996 Damages

Act allows the Lord Chancellor to set the discount rate for that jurisdiction

thus obviating the requirement for the court to determine the rate. The rate

was first set in 2001 at 2.5%, which remained the rate until 2017.

12 It is generally accepted that a

recipient of damages for personal injuries should not be required to invest the

damages in high risk investments. However, Wells

v Wells went further, and this, and other cases, established

that the plaintiff was entitled to invest his or her damages in extremely low

risk investments including gilts i.e.

index linked government stock (“ILGS”).[5]

13 The fact that a plaintiff may choose to

invest in other securities offering a higher rate of return was held to be

irrelevant to the calculation of lump sum damages. Consideration of what is actually

done with an award or how it might be spent or invested was not to be taken

into account.

14 It was generally agreed that the

discount rate should not frequently be adjusted.

15 When the discount rate of 2.5% was set

by the Lord Chancellor in 2001, ILGS yields were good and well in excess of

inflation. The 3-year average yields on gilts with 5 years to maturity was

2.46% in 2001. With an appreciated 15% reduction for tax giving a yield of

2.09%, the discount rate was set at 2.5%.

16 However, events subsequent to the

financial crisis from 2008 onwards led to a drastic fall in ILGS yields. Those

wishing to invest conservatively had to accept much lower rates of return. By

this time the historic average ILGS yields had fallen into the negative, leading

to the Lord Chancellor being advised that the discount rate, if it was set

using the same methods used in 2001, should be between –1, and –0.5%.

In those circumstances, the Lord Chancellor, constrained as she was by the

approach taken in 2001, set the rate at –0.75%.

17 This led to controversy, particularly

given the effect upon insurers and the NHS, where the cost of medical

negligence claims suddenly substantially increased. The new rate set by the

Lord Chancellor was also much lower than discount rates set in other countries.[6]

18 Setting the discount rate in England and

Wales has become, as recent experience has shown, a controversial and lengthy

process.

Jersey

19 It was generally agreed that it would be

sensible for Jersey to pass a law providing for a statutory discount rate. Most

common law jurisdictions have done so. Not to have such a discount rate results

in uncertainty for plaintiffs, defendants and insurers, and makes it worthwhile

for parties to contest the discount rate on a case-by-case basis.

20 The most important case for the Channel

Islands in respect of the discount rate was the Guernsey case Simon v Helmot.[7]

In this case, all parties proceeded on the understanding that the Wells v Wells approach was to apply. However,

on the basis of expert evidence, the court decided that the return on ILGS

investments was lower than when the Lord Chancellor had set the England and

Wales discount rate in 2001, and that Guernsey inflation rates (particularly

for earnings) should be taken to be significantly higher than those in the UK.[8] The

result was that Guernsey Court of Appeal and the Privy Council decided that the

relevant discount rates for Guernsey should be substantially lower than the

then prevailing discount rate set by the Lord Chancellor in England and Wales. This

eventually resulted in a case in Jersey in 2018 where the plaintiff’s

advocates were arguing for even lower discount rates (as low as –4.5%).

Simon

v Helmot and periodical payments

21 It was recognised by the Privy Council

in Simon v Helmot[9] that periodical payment orders are the

fairest way of assessing damages. Periodical Payment Orders (“PPOs”)

provide for damages to be paid periodically as opposed to being paid in a

single lump sum. So if a court decides that a plaintiff will need

£100,000 per year to pay for care costs for the rest of his or her life

the court does not need to worry about investment returns or life expectancy if

the sum is being paid annually.

22 The advantages of PPOs include:

(a)

it is not necessary to estimate life expectancy;

(b)

there is no worry that the damages will run out before the plaintiff dies;

(c)

there is no need to speculate on investment returns; and

(d)

there is no concern that there might be a surplus at the end of the

plaintiff’s life or when the injuries resolve. Generally courts err on

the side of caution, and there is frequently a considerable lump sum left when

the plaintiff dies which may have the effect of inadvertently enriching third

parties.

23 However, there are legitimate concerns

that arise from awarding damages by way of PPOs, including the following:

(a)

it is necessary for the order to be secure for the whole term. Many corporate

defendants will simply cease to exist over the course of, say, 50 years.

Accordingly orders can only be made against public bodies or particular

insurers;

(b)

insurers often prefer to pay a single lump sum as it gives certainty of

exposure;

(c)

PPOs have proven inflexible, and for a long time it was a feature of English

legislation that it was only possible to vary an order once. This had the

consequence that parties were reluctant to apply to vary an order as they knew

it would be their only opportunity to do so; and

(d)

a lump sum ends the relationship between plaintiff and defendant, whereas PPOs

necessarily continue the relationship, creating uncertainty and additional

cost.

24 Prior to the enactment of the Law PPOs

could be ordered in Jersey by consent.[10] It was

not as clear whether customary law permitted a court to make a PPO where one of

the parties objected. The possibility had been suggested (obiter) by two of the judges in Simon

v Helmot.[11] The

Attorney General argued as partie

publique in the case of X v Minister

of Health & Social Services in 2018, that there was customary law authority

allowing the Royal Court to develop practice so as to allow such payments to be

made without legislation, however the case settled before judgment.[12]

Other jurisdictions

25 Legislation which exists in other

jurisdictions in part informed the contents of the damages legislation which

was ultimately adopted in Jersey. Consideration of comparative law was greatly

assisted by an extensive briefing paper prepared for the Ministry of Justice by

the British Institute of International and Comparative Law (“the BIICL paper”).[13]

26 The appendix to this article contains a

bar chart showing various discount rates for jurisdictions, as considered in

the BIICL paper. As the chart demonstrates, the discount rate in England and

Wales (and the discount rate contended for by the plaintiff in the case X v Minister of Health & Social Services

in 2018)[14] was

an outlier when compared with the rates established in comparable countries. It

can be seen that the discount rates in the Australian states generally vary

between 5% and 6%, the rate in Spain is 3.5%, the Canadian rates are generally

between 2.5 and 3%, Hong Kong has three discount rates depending upon the

period during which the loss is anticipated to endure (0.5%, 1% and 2.5%),

South Africa and the Isle of Man hold to the discount rate of 2.5% and in the

Republic of Ireland the rate, depending upon the component of the claim, is 1%

or 1.5%.

27 The Australian rates show that in these

states the principle upon which compensation is ordered is different from that

which applies in England and Wales. In Australia the discount rate is a

compromise between a discount that accurately reflects the real rate of return

a plaintiff might obtain by investing in reasonably safe investments, and one

that takes into account the fact that too low a rate of return might have

adverse consequences on the provision and cost of liability insurance.

28 Most jurisdictions have a single

discount rate. However the English and Scottish legislation (the latter in its

Damages (Investment Returns and Periodical Payments) (Scotland) Act 2019) have

the power to set different rates. Furthermore, certain jurisdictions do have a

split discount rate, including Hong Kong and Victoria, both of which have a

split rate depending on the number of years of projected loss. Victoria and

Tasmania have split rates based on the type of accident and Quebec and British

Colombia rates split depending upon the type of loss (for example earnings or

care costs).

29 Different jurisdictions have adopted

different approaches as to who should set the discount rate. In Ontario, it is

set by the Attorney General. In other jurisdictions it is often set by the

Government. In England the rate is set by a Minister (the Lord Chancellor) and

in Scotland the rate is to be set by a rate assessor who is appointed by the

Government Actuary.

30 The amount of discretion in the rate

assessor varies depending on the model. The process for setting the rate in

Scotland for example is strictly prescribed. The rate of return must reflect

the return that could reasonably be expected to be achieved by a person who

invests in a “notional portfolio”

for a period of 30 years. The notional portfolio is prescribed in a table which

sets out in precise percentage terms the combination of investments which

includes cash, gilts, equities, bonds, investment grade credit and property.

Plainly the more prescriptive the legislation, the less discretion is in the

hands of the rate assessor.

Key aspects of the Law

31 With one caveat, the Law was enacted as

drafted. The Law underwent a lengthy scrutiny process prior to being debated.

32 Article 2 of the Law provides a

mechanism for setting the discount rate. It was thought necessary and appropriate

for the Law to set the discount rate in statute at the outset in order to

ensure that the experience in England and Wales of a lengthy delay in setting

any discount rate should be avoided. In order to prevent such a delay, Article

2 introduces two statutory discount rates which took immediate effect. The

rates are:

(a)

0.5% in respect of future pecuniary loss expected to be occurred for a period

not exceeding 20 years;

(b)

1.8% in respect of future pecuniary loss expected to be incurred for a period

exceeding 20 years.

33 Nonetheless, there needed to be a sound

evidential foundation for the setting of the initial discount rate(s). This

evidential foundation was referred to in the report accompanying the proposition

containing the draft Law and exhibited as appendix 2 to the report. It

consisted a review conducted by the States of Jersey’s Senior Economist

and Director of Treasury Operations and Investments which itself referred to a

report prepared by the UK Government Actuary’s Department prepared for

the Ministry of Justice in July 2017.

34 This last report (“the GAD

report”) was the outcome of an analysis of the investment strategy

actually adopted by plaintiffs having received advice from investment advisers

as opposed as to the theoretical (and impractical) investment of the whole of

sum in gilts.

35 This analysis showed that the returns

that plaintiffs received would very much depend upon the investment strategy

adopted by their adviser. The GAD report demonstrated that the proposed discount

rates considered were lower than the median return on many investment

portfolios over the longer term. The consequential level of over-compensation

depended upon the investment strategy selected and ranged between 35% and 48%.

The two principal investment strategies selected by the GAD report were broadly

derived from consultation with wealth and investment managers. The report

showed, for example, that gilts were projected to give a negative annual return

over the next 50 years whereas, by contrast, if a fund was invested in UK

equities over a 30-year period, then the effective real return would be RPI

plus 2%, which would allow a discount rate of 2% to be selected, resulting in

no under or over compensation.

36 The GAD report model featured two investment

strategies. First, an average or typical portfolio invested in by personal

injury plaintiffs, based on evidence from wealth managers, investors and

investment advisers, which corresponded most closely with a low risk strategy. Secondly,

a separate portfolio representing again an average or typical portfolio

invested in by personal injury plaintiffs, based on evidence from wealth

managers and investment advisers, which corresponded to plaintiffs who would be

described as taking more risks than plaintiffs adopting the first portfolio.

Nonetheless both, overall, were low risk investment strategies. The GAD report

stated there is no universally accepted definition of a “low risk

investor” or “a low risk investment strategy”.

37 The expected real returns for the two

portfolios over 10 years were 0.6% and 1.3% respectively, over 20 years 1.2%

and 1.9% respectively, and over 50 years 1.6% and 2.3% respectively; these

figures all being net of inflation.

38 The GAD report indicated that these

figures demonstrated—

“the importance that the duration of the award

is likely to have on claimant outcomes—expected returns over shorter

periods are lower, meaning that claimants that adopt a given strategy with

shorter awards are more likely to be under-compensated.”[15]

39 It was this finding that led directly to

the proposal that there should be two discount rates for Jersey.

40 The analysis of the GAD report by the

Senior Economists and the Director of Treasury Operations and Investment

considered the two assumed portfolios, and agreed that it was unrealistic for

Jersey to follow a “no risk” approach on the footing that

plaintiffs should be treated as if they invested solely through gilts.

41 It was noted that the performance of the

two portfolios led to the recommendation that the discount rate be separated

into two rates—one for short term losses of less than 20 years and one

for long term losses of 20 years or more. This would yield discount rates of 1%

and 1.8% respectively. However it was then necessary to consider whether or not

the UK projected returns (net of UK RPI) should be adjusted having regard to

any difference in historical and future inflation between Jersey and the UK.

42 The Jersey reviewers suggested an

adjustment to the discount rate to reflect the difference in inflation over the

shorter period by reducing the discount rate by 0.5% (to 0.5%). Over the longer

term it was expected that the inflationary differential between Jersey and the

UK would revert to historic norms and that no adjustment should be made. It is

unlikely that Jersey and UK prices should grow apart exponentially over future

decades, as would be the case if it was assumed that Jersey would have a

permanently higher inflation rate.[16]

43 Accordingly the recommendation of the

Jersey experts was that the two initial discount rates should be set at 0.5%

and 1.8% respectively.

44 As to the method of setting the discount

rate, art 2(3) of the Law provides the Chief Minister may, after consultation

with the Bailiff, amend the discount rate. It was thought that the correct

balance between executive and judicial power which is necessary to ensure that

on the one hand public funds were properly protected, and the other that the

interests of victims as litigants were properly catered for, was struck by this

arrangement.

45 The remainder of art 2 of the Law deals

with the matters to be taken into account when setting the discount rate. In

this regard the States have not yet made regulations which provide detailed

rules for the setting of a discount rate, although this may follow, if

necessary, in due course.

46 Without prejudice to the generality of

the regulation making power at art 2(4), art 2(5) sets out that the regulations

may make provision for a number of matters including, for example, the process

for determining the discount rate and any requirement for consultation.

47 The only express criteria that the

regulations must provide for is set out in art 2(6) which provides:

“In making provision in Regulations for

determining the discount rate, the States must take into account the return to

be expected from a lower risk diversified portfolio of investments.”

The purpose of this provision is to ensure that

whatever regulations the States ultimately adopt, the basket of investments by reference

to which the discount rate should be calculated should not contain only gilts

but a “diversified portfolio of investments” which would be

“lower risk” as opposed to “low risk”.

48 Finally, art 2(7) provides that “The

discount rate must not be amended to a percentage less than 0%.”

49 A similar provision was identified in

other jurisdictions and commended itself to the Government and ultimately the

States, on the footing that it would ensure that there was no risk of a

negative discount rate being set with the consequences that might have. It was

thought that it would be only in extremely unusual circumstances, such as

economic collapse, that there would be evidence of longer term inflation

exceeding investment returns and, in such circumstances, it would be wrong for

the interests of plaintiffs to be preferred to the interests of other

individuals faced with similar economic circumstances.[17] It would

only be in those circumstances that the principal of compensation would be

deviated from.

50 Article 3 and certain provisions of the

Income Tax (Jersey) Law 1961 allow the States to make regulations amending the

Law to make provision for the taxation (including exemption from taxation) of

lump sum payments for future pecuniary loss awarded by a court in personal

injury cases.

51 Article 4 places periodical payment

orders on a statutory footing.

52 Article 4(2) provides that—

“A court awarding damages for future pecuniary

loss in respect of personal injury may make an order that damages must wholly

or partly take the form of periodical payments.”

53 Article 4(3) provides that a court may

not make such an order unless it is satisfied “that the continuity of

payment under the order is reasonably secure.”

54 What amounts to reasonable security is

set out in art 4(4) of the Law, and includes orders enforceable against a

Minister, orders protected by a scheme established under any jurisdiction which

gives protection equivalent to the scheme established under s 213 of the

Financial Services Market Act 2000 of the United Kingdom, or it is subject to a

guarantee given by a Minister for Treasury and Resources.

55 Article 4(8) of the Law is significant

in that it provides that—

“A person who has an interest in the making or

receipt of a payment under a periodical payment order may apply to the court

for a variation of the provisions of the order on the ground that there has

been a material change of circumstances since the order was made.”

56 This gives a wider power of variation

than appears to be applicable in other jurisdictions, and certainly in England

and Wales, in respect of the circumstances in which an order can be varied. There

was no attempt in the legislation to define “material change of

circumstances”. This has been the subject of some criticism on the basis

that insurers will be uncertain as to the circumstances in which a PPO can be

varied.[18] That

said, there is a good argument to the effect that the courts will, in the

perhaps unusual circumstances where such an application was made in Jersey, be

able to give guidance through case law as to what amounts to a “material

change in circumstances”. In England and Wales, only certain changes can

lead to a variation of a PPO, and a particular type of change can only lead to

one variation during the lifetime of the PPO.[19] A

Northern Irish case where the same rules apply shows that such inflexibility

has led to attempts to side-step the statutory regime by building possible

variations in the original PPO.[20] Rather

than delay whilst seeking to develop a perfect regime, or import an imperfect

English approach into Jersey, it was thought better to give a broad discretion

to the Royal Court.[21]

57 The only amendment to the Law in draft

form was made to art 4 in respect of the States’ regulation making power

to make provision for when there has been a material change of circumstances

and when an application can be made to vary a PPO. I return to this amendment

below.

58 Article 5 of the Law deals with the

definition of public bodies for the purpose of making PPOs against such bodies

and art 6 deals with the transitional provisions in respect of actions for

damages instituted prior to the commencement of the Law. This was an important

provision in order to ensure that such human rights issues as might arise from

the Law applying to pending cases could be avoided. This may have been an

unnecessary precaution given the English High Court decision in R (Assn

of British Insurers) v Lord Chancellor, rejecting the need for transitional provisions when the discount rate

was reduced in England in 2017 from 2.5% to –0.75%.[22]

However, given the importance of the Law, it was necessary to prevent human

rights arguments delaying the legislation’s passage to Royal Assent, or

for doubts over its application to persist after its registration.

59 The discount rate applies to court

orders for damages made on or after the commencement date unless the court

considers that to do so would breach the rights of a party to an action under art

6 of the European Convention of Human Rights.

60 Such restrictions do not apply to PPOs. A

PPO could be made in any case, even by a court on appeal subsequent to a trial

that took place before the commencement date. There was no difficulty in

following this approach as the Privy Council in Helmot v Simon had indicated that PPOs would normally be a fairer

way of disposing of a matter than a lump sum award. Lord Dyson put it simply

and firmly:[23]

“In my view, periodical payments are obviously

the most accurate (and therefore the fairest) way of taking future inflation

into account in the assessment of damages.”

61 It has not been suggested in any case

which has been determined since the coming into force of the Law that the

provisions of the Law do in fact amount to a breach of any litigant’s

human rights.

The scrutiny

process

62 The Corporate Services Scrutiny Panel

published a report on 28 January 2019 on the reforms. The panel received 13

submissions to its review, many of which offered detailed and technical

comments on the draft Law. Three public hearings were held in order to take

oral evidence. All the evidence received was published on the States Assembly

website. The chairman of the panel noted and acknowledged the need for

legislation in this area and that most stakeholders supported the principles of

a new Damages Law.[24]

63 The contributions made during the

scrutiny process will not be described in detail. However, some were valuable

as they came from parties operating in other jurisdictions with experience of

both a statutory discount rate and PPOs.

64 The response of the Association of

British Insurers (“ABI”) was supportive of the draft Law. The

following extracts are of interest:[25]

“2. The insurance industry fully supports the

principle that seriously injured claimants should receive 100% compensation. The

principle of full compensation requires a system that neither over nor under

compensates claimants. However, this is best achieved using methodology for

setting the rate which reflects a real-world approach to investment, rather

than a purely theoretical approach to how claimants invest their damages as the

current framework allows for.

3. The current discount rate in England, Wales and

Scotland of minus 0.75% reflects the application of a purely theoretical

approach [. . .]

4. Such an approach to setting the Discount Rate does

not deliver a rate that reflects reality. No properly advised claimant would

ever invest in ILGS alone, nor any single asset that would deliver a negative

return for the long term.”

65 The ABI expressly supported the proposal

that the discount rate should never be set below 0% and noted that this “underpins

real world investment decisions and is supported by the Senior

Economist’s advice.”

66 They went on to say—

“The ABI also supports the policy of reasoning

for this decision noting that it would not be appropriate for damages awards to

be “recession proof” when all other areas of public provision and

private services are not.”

The ABI went on to observe that they understood—

“that the current approach of the courts in

Jersey has often led to claims at levels which would exceed the likely limit of

indemnity of any cover held or available in this market.”

67 The ABI also supported the “dual

approach”, noting—

“A dual approach should ensure that those claimants

with a shorter investment period, who cannot rely as easily on returns from

investment in equities, are not undercompensated. A higher long term rate is

appropriate.”

68 The ABI went on expressly to support the

two rates chosen as set out in art 2 of the Law and noted that those were

variations present in the Ontario and Hong Kong legislation. They observed:

“20. A dual rate mechanism recognises the

problem of using a “single” discount rate to determine lump sums

that are often calculated as the present value equivalent of very long payment

streams (typically 50 years plus). To assume that real yields will perpetually

remain at the current depressed levels in effect ignores the longer term

average returns that have been achieved historically, and that are likely to be

achieved again in the future.

21. The dual rate overcomes this flaw by setting rates

that recognise that settlements covering shorter durations may require

different assumptions from those covering longer durations.”

69 It was noted that the Ontario and Hong

Kong legislation differed and that the consensus appeared to be for a short

term rate of 10 to 15 years, and in that regard “The draft Law’s

combined proposal of 20 years and a rate of +0.5% represents a suitable

compromise.”

70 The ABI went on to observe that there

was a good argument for the short term rate to be more likely to be susceptible

to external factors and therefore more frequent review—noting the

proposal that the short term rate be reviewed every five years in England and

Wales. As to the long term rate that should be revisited but “should

rarely change, since it should not be affected by short-term or even

medium-term factors”. It was noted that the Ontario long-term rate had

not changed and had remained at 2.5% since 1981.

71 Interestingly, the ABI said that their

data showed that for claims with a value exceeding £1,000,000 the “average

life expectancy of the claimant is 46 years.” Accordingly this means, for

the Jersey context, all large cases are likely to be dealt with under the 1.8%

discount rate. Bearing in mind Jersey’s use of the GAD assumptions which

focused on the average period of years which a lump sum would be needed to last

being thirty years, the ABI view was that the long term rate should be “higher

than 1.8% and around the 2.5% net rate applied in Ontario since 1981.”

72 Accordingly their view was that overall

the provisions in the new Law were appropriate. The ABI noted that no allowance

had been made for investment management charges as part of the breaks of the

exercise. They said this was appropriate because plaintiffs purchasing such

services will tend to keep the cost to a minimum; a low risk portfolio involves

less active management meaning low management charges and a portfolio requiring

more active management should generate higher returns.

73 The ABI agreed that the new rate should

apply to existing cases as that was how the common law operated. They noted—

“The rationale is that the application of a

discount rate in an individual case is always a prospective exercise, looking

at the likelihood of future returns—even if it gives the appearance of

increasing or reducing the lump sum award.”

74 However, the ABI did feel that the

provisions in relation to PPOs lacked the necessary clarity as to the

circumstance in which they could be varied. Further, they felt this matter

should be dealt with by way of legislation and left to Rules of Court.

75 A Jersey law firm with experience in

acting in personal injury cases, including representing the plaintiffs in the X Children case, also provided a contribution.[26] They

welcomed the proposal of a statutory system by which the discount rate was to

be set and accepted that it would reduce the cost involved in litigating claims

by avoiding the introduction of expert evidence as to the appropriate rate.

They opposed some of the provisions in the draft Law including the 0% floor for

the discount rate and the failure of the Law to stipulate the frequency of

review of the rate. They were also concerned that the Law did not provide the

courts with the power to set a different discount rate for a particular case if

justice required it, which had been a feature (albeit never used) of the United

Kingdom’s Damages Act 1996, and is also found in other jurisdictions. The

GAD report was criticised as providing an inappropriate evidential foundation

for setting the Jersey discount rate, and it was asserted that the approach of

calculating the discount rate on the footing that a portfolio consisting

largely or wholly of ILGS should be used, whether or not it represented what

plaintiffs did with their fund in the real world.

76 The statutory regime for PPOs was

welcomed, and in particular it was noted that the possibility of varying a PPO

where there has been a material change of circumstance was a welcome

improvement on the English position where, pursuant to the Damages (Variation

of Periodical Payments) Order 2005, the circumstances in which a PPO could be varied

were tightly restricted and only one application to vary could be made in

respect of each specified disease or type of deterioration or improvement

identified by the court when making a PPO. Under English legislation there was

no power to order unrestricted variation in instances such as when the payments

under the original PPO were insufficient and/or because care costs had

escalated over time.

77 It was argued that the transitional

provisions were not compliant with the European Convention on Human Rights as

they would infringe the common law rights to a lump sum in damages. As set out

above, there have been no problems in the United Kingdom in making changes as

to how to calculate the proper amount of compensation without transitional

effect.[27]

78 The submission made by DAC Beachcroft,

an English law firm with extensive personal injury litigation experience,

welcomed the draft Law.[28]

79 They noted that the then current

discount rate in England, Wales and Scotland of minus 0.75% reflected the application

of a purely theoretical investment approach, the then Lord Chancellor in

England & Wales having taken the view that the decision should be based in Wells v Wells,[29] and

calculated the discount rate based on investment solely in ILGS. However, no properly

advised plaintiff would ever invest in ILGS alone, and there was absolutely no

evidence, when reducing the discount rate to –0.75% in March 2017, of any

plaintiffs who had invested their lump sum award solely in ILGS. As a result,

they believed that the then current discount rate over-compensated plaintiffs.

They also suggested that the rate of return on ILGS had been affected by a

number of factors including quantitative easing by the Bank of England,

excessive demand over supply, the regulator requirements on pension funds and

the influx of foreign capital during the financial crisis.

80 DAC Beachcroft supported the 0% floor

for the discount rate and the policy reasoning for the decision.

81 They observed that by basing the

discount rate on a real world approach to investment, the draft Law aimed to

provide plaintiffs with full compensation, whilst considering the importance of

protecting the public from the cost of over-compensation. The dual rate was

welcomed and they, like the AIB, observed that the short term rate is more

likely to be susceptible to external factors and may therefore require more

frequent review. As to the long term rate, that should only be changed if there

is evidence of a permanent shift in returns expected over the longer term.

82 As to PPOs, their view was that the

draft Law was too wide in terms of not limiting the circumstances in which an

order could be varied.

83 Various individuals also provided

submissions to the Scrutiny Panel including members of the medical community.

One wrote expressing her concerns in relation to the increased insurance rates

that she was facing and suggested that the States should look towards Australia

where a crisis had provoked change and appropriate discount rate had been set.

She and other medical practitioners suggested a rate of 4.5% or above was

necessary.[30] It

was suggested that any other approach would create a crisis in general

practice.

84 The British Medical Association

(“BMA”) (and Hempsons, an English law firm specialising in medical

negligence) made a submission which included describing the “crisis in

clinical negligence funding in England.” The huge increase in the level

of damages for personal injury claims in England and Wales was evidenced. This

was attributed to the change in the discount rate which had provoked “a

surge in inflationary expectations.” They recommend legislation for a

positive discount rate not linked to risk free investment (ILGS), noting the

common law use of a 4.5% discount rate until 1999, and that “people who

recovered compensation on that basis did not run out of money.”[31]

85 It was also recommend that the cost of

care, other therapies and accommodation should be removed as recoverable heads

of loss, and that plaintiffs should make the use of services provided by the

States instead. It was said—

“The problem with the contrary assumption that

we have seen in England is that every claimant demands a one-patient

institution, which was proved to be a prodigiously expensive way of providing

care.”

86 A cap on damages was recommended for

consideration. Tables produced by the BMA/Hempsons Solicitors, illustrated the

drastic effect of different discount rates. Assuming a 50 year term of loss,

with a discount rate of –2%, the multiplier was 86, whereas a discount

rate of +5% yielded a multiplier of 18.7. Jersey was invited to follow the

Australian approach to the discount rate, reject the notion of 100%

compensation, and strike a reasonable compromise to take into account the need

for the medical profession to deliver and remain able to provide their

services. The suggestion that to change the Law as proposed might give rise to

a claim that the human rights of a plaintiff whose case was being progressed

through the courts was rejected.

87 The Forum Insurance Lawyers Corporation

(“FOIL”) confirmed that they accepted both the 100% compensation

principle and at the same time welcomed the provisions of the new Law including

the approach to setting the rate and the dual rate.[32]

88 FOIL said that the report from the GAD

indicated that the rate of –0.75% yielded 95% of plaintiffs being

over-compensated by an average of 35%.

89 By contrast, an English firm of personal

injury lawyers took a different view. They suggested that the proposed discount

rates were too high, and that the Jersey Government was wrong to rely upon the

GAD model portfolio.

Amendments made to the Law and the States

debate

90 The scrutiny process led to

reconsideration of the draft Law, and one significant alteration was made as

follows:

91 Article 4(8) of the draft Law allowed

for variations to PPOs where there was a material change of circumstances. It

was recognised that the draft Law did not define what those material changes

were, however, it was envisaged that the court would not have any difficulty in

determining what amounted to a “material change of circumstances”.

To that end, the draft Law was amended to provide a regulation making power to

enable the Assembly to prescribe the conditions under which a PPO could be

varied.

92 The amendment empowers the States to

make provision for determining when there has been a material change of

circumstances and when an application can be made for variation, including

providing for:

(a)

factors to be taken into account in determining whether there has been a

material change of circumstances;

(b)

any period of time that must elapse before an application or subsequent

applications are made, with reference to such factors as may be specified in

the regulations, including the nature of any change of circumstances or

otherwise;

(c)

when the leave of the Royal Court is required to make an application, either in

all circumstances or in such circumstances as may be specified.

93 There was also a small amendment to art

2 in relation to the content of regulations which might be made for the

purposes of making provisions in respect of the setting of the discount rate.

Response to the Law

94 So far the response to the Law has been

positive.

95 The new Law has had a beneficial effect

on negotiations that the Government of Jersey has had in renewal of its

insurance premiums.

96 In the run up to the debate on the Law,

members were alerted to a number of pending claims against the States of Jersey

which would be affected by the Law if passed. Of those cases, one settled for

significantly less than was originally anticipated. This was a result of a

complex range of factors, but it was clear that the Law played a significant

and integral role in reducing the overall liability. In relation to the other

cases, any trial will certainly be reduced in length and it is likely that any

lump sum that may be awarded will also be reduced as a consequence of the

statutory discount rate.

97 The reduction in the value of sums

claimed in all cases affected by the Law has so far been to the tune of tens of

millions of pounds. No claims have been made to the effect that

plaintiffs’ human rights have been adversely impacted.

98 As to the position in England and Wales,

after a period of approximately two years the Lord Chancellor has recently set

a discount rate of –0.25%. The rate has been subject to criticism in some

quarters and welcomed in others.

Robert

MacRae QC was HM Attorney General for Jersey between May 2015 and January 2020. He has now taken office as Deputy Bailiff of

Jersey.

Appendix

Discount rates across

various jurisdictions—comparative bar chart (information correct at date the Law was passed)

Discount rates across

various jurisdictions—comparative bar chart (information correct at date the Law was passed)